Paseo de la Reforma is a reflection of Mexico City’s culture, a space where a Genoese sailor, the last Aztec tlatoani, a representation of a Roman goddess, a winged victory, and a light stele coexist. In the same place, a group of tourists taking pictures, car and bike traffic, several quinceañeras in a photo shoot, helicopters landing on skyscrapers, people in suits out breathing some air, and a manifestation of naked people dancing to the rhythm of drums; this is a snapshot of the great city avenue.

Streets are entities that transform constantly, they are one in the morning and a very different one in the afternoon, at night, and on weekends. They also change as years go by: pavements are fixed, trees grow, they are connected with other streets. People travel across them, coexist, and create stories. All this collective imaginary and the scenes that take place there give personality and life to these spaces.

Reforma is, undoubtedly, Mexico City’s most important street, culturally speaking. Its transformations have been constant, and more than just a street, it is a history book.

The history

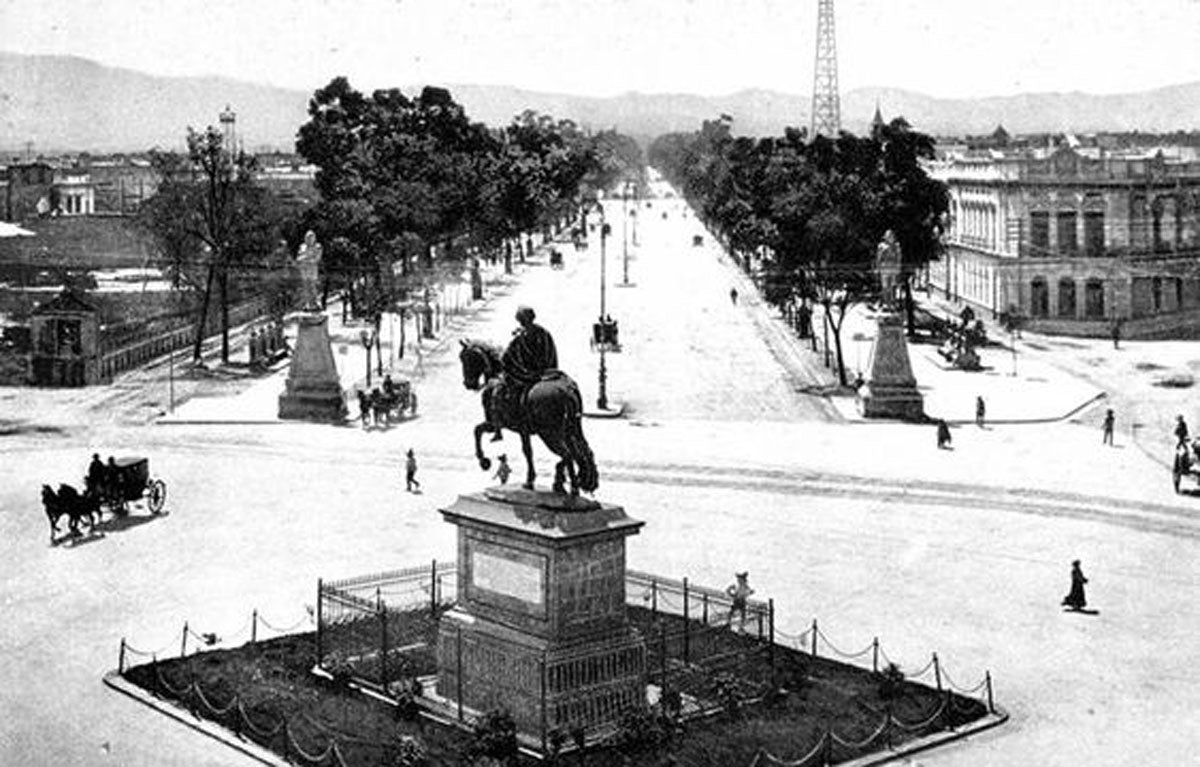

In 1864, Mexico was undergoing the second French intervention and as a consequence, the Second Empire established in the country led by Maximilian of Habsburg, a well-intended character with all circumstances against him. This period lasted almost four years, among its different political and cultural projects, one of the most important related to the embellishment of the city was Paseo de la Emperatriz, without a doubt, a boulevard that would connect the Imperial Palace (National Palace) with the Chapultepec forest, just by the foot of the Castle, house of the imperial couple at the time. The original name honored Empress Charlotte, the plan of this urban element would be inspired by the boulevards of the cities in Western Europe. During the project assessment, the decision was made for the avenue not to reach the Imperial Palace, due to the existing urban plan, it would begin where the Caballito is currently located, instead. During this time, the road was restricted to the imperial court use, although back then there were practically no adjacent buildings, traffic was mainly composed of horse carriages and pedestrian sidewalks were not needed.

The second Mexican empire ended in 1867, the Republic was back. Juárez returned from the north to take the presidency back. As for the famous avenue, main character of this text, it was first called Paseo Juárez. The president did not love the idea, so he named it Paseo de Degollado, honoring General Santos Degollado. In 1872, he presented the initiative to definitely name it Paseo de la Reforma. The work continued during this stage, the road was officially open to the public, pedestrian ridges were added, and trees were planted (eucalyptus, willows, and ashes). Four roundabouts were added between what is today known as La Palma and Avenida Juárez. The first residential neighborhoods began settling by the sides of the avenue.

When Porfirio Díaz took office in 1876, he had the policy to modernize the country through the embellishment of the cities. It is important to highlight that General Díaz and his consultants pushed nationalist ideas, inspired by the French positivism; by the hand of this, a new value for “Mexican style” culture and art would emerge, which evidently was not limited to pre-Columbian cultures from the area, it was not an adaptation of the culture brought by Spain either, rather it was seen as a syncretism that covered a gigantic and complex cultural spectrum, completed with other cultures which in some way, affected this blend. The artistic style from Western Europe was the aesthetic reference, mainly from France and Austria. During the Díaz administration, this style was promoted across the country, where it was tropicalized with elements and narratives from Mexico.

It was during this time that the resolution was reached to turn Paseo de la Reforma into a space with sculptural monuments reminiscent of the nation’s historical times and characters. The first two monuments in this program were Cuauhtémoc and Christopher Columbus, each one at the head of a roundabout. Within the same program, trees were planted to limit pedestrian walkways. Also, the iron gates known as Puerta de los Leones were placed, the first public lighting was set along with a series of benches that still exist today. Along the avenue, a series of pedestals were placed, which would originally serve as foundation for planters and Greek gods. By suggestion of writer Francisco Sosa and providing congruence to the original program, it was finally decided to put up sculptures of Mexican illustrious people, mainly from the time of the reform; each state of the Republic would submit names in order to choose such personalities, and in this way, the first 24 sculptures were selected, which would be intercalated with bronze-cast vases.

The Cuauhtémoc roundabout became an ode to pre-Columbian cultures, a monument led by the last Mexican tlatoani and which mentions other warriors and leaders from the time, like Cuitláhuac, Cacama, Tetlepanquetzal and Coanacoch. Its style is inspired by pre-Hispanic elements and construction principles.

On its part, the Columbus roundabout shows the Genoese sailor in a protagonist fashion, considered to be America’s discoverer. This monument celebrates the union of the old and new continents and the cultural syncretism that would lead to the Mexican culture. As secondary figures are Fray Pedro de Gante, Bartolomé de las Casas, Fray Juan Pérez de Marchena, and Fray Diego de Deza.

The pedestals with illustrious characters have expanded during Reforma’s different growth stages, there are currently 72. They have followed the line of being chosen by the administrations from the states. Ironically, most of these characters are not relevant to this day and remind us that often history is told by the winners and by those who manage to, in some way, be present.

Around the same time, the neighborhoods named Cuauhtémoc, Americana (Juárez), Condesa, Roma, Arquitectos (currently San Rafael) began developing tangentially, and with time they would populate the landscape around the avenue.

An undoubtedly important event was the celebration of 100 years since the Independence, where a series of improvements were made to the avenue, it is also under this celebration that the monument known colloquially as The Angel was inaugurated. The Independence Column, which at first used to celebrate Mexico’s centenary as an autonomous country, is much more than that today; it represents the country’s freedom, progress, strength, permanence, and happiness. It has been transformed as Mexico City’s symbol par excellence and it is a reference point for celebrations and gatherings.

Porfirio Díaz’s government did not last much more time and soon the Revolution reached the capital city, clearly crossing Paseo de la Reforma. Some residences that ran along the avenue were damaged during the battles along with other secondary monuments; however, the main elements were not severely affected. There was no significant change during this period; however, the lands near the recently emerged neighborhoods began to rapidly increase their occupancy, residences were built, mainly high-end ones, inspired by the Neoclassic, Art Nouveau, and French Art Déco architectural styles.

In the late 1920’s, the Chapultepec Heights area was consolidated, currently known as Lomas de Chapultepec, a top class area, where many people who managed to avoid the revolution or got rich thanks to it, bought properties. This area made it necessary to expand the avenue, which will later be known as west Reforma.

With the 1940’s came the whole paving of the road and the central ridge was established, inaugurating the monument to Diana and beginning an unfinished project in the crossing with Avenida Insurgentes.

Regarding Diana the hunter, her original name was The Archer of the Northern Stars, clearly inspired by Diana, the mythological being, Roman goddess of hunting. Poetically, the title suggests a woman who instead of hunting for prey, aims her arrows at the stars. Even though the historical reference is far from the Mexican culture, it was a symbol adopted as Mexican and soon people began to call it simply “La Diana”. This piece has changed its location three times; at one point, a skirt was added and later removed. Due to the damages caused by these modifications, a new piece was cast, which is currently on exhibition. This monument can be related to the concept of women and the progressive ideas in the country.

During the 50’s decade, the first tall buildings emerged in the area, traffic increased, adjustments were made to lanes and the pedestrian walkways were fully paved. The 1957 earthquake caused damages to the city, the falling of the Angel among them, which was promptly repaired and placed again at its place.

The oil fountain, inaugurated in 1952 used to be surrounded by a small garden with endemic vegetation. The piece is reminiscent of the oil expropriation, speaks about a growth period and bets for the country, celebrates the strength to make an industry thrive. It tells the way in which the joint work of technicians, specialists, workers, and politicians led to one of the greatest industrial successes in Mexico’s history.

During the 60’s and70’s decades, Mexico was in a great place, the value of the Mexican Peso was high, the country had been chosen to host the 1968 Olympics, people talked about a Mexican miracle. In the capital, Ernesto P. Uruchurtu was the mayor and there were organization and budget for many works and projects. One of these plans, which at first seemed a little unreal was called “El Proyectazo” (the big project), which included, among other things, an expansion, mainly functional, of Paseo de la Reforma, from El Caballito to the Peralvillo roundabout. In order to finish this project, some constructions and existing works had to be demolished and the previous urban trace had to be modified. With this expansion, three new roundabouts were added, where monuments honoring Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, and Cuitláhuac were placed, also adding lateral sculptures honoring illustrious characters, following the original plan. Additionally, seven small roundabouts were added in the west Reforma area.

During the 80’s and 90’s, the transformations continued. The Charles 4th equestrian statue, which at some point marked the beginning of Paseo de la Reforma, was relocated in the Manuel Tolsá square. In the corner with Sevilla street, the Cutzamala roundabout was built, to honor the main water distribution center in the city, this construction was there for more than 10 years, since Diana the hunter was later placed here. In 1985, the most devastating earthquake in Mexico’s modern era took place, causing the collapse of many buildings located along the corridor. Undoubtedly, the landscape suffered drastic changes.

Years after the Caballito sculpture was inaugurated, located in the area previously occupied by Charles 4th equestrian statue and, from habit, this area always kept its name. The monarch’s sculpture, even though it was not placed originally for that purpose, became a historical element with time, which made reference to the Colony and viceroyalty eras, showing the Spanish King at the time. Later, the mega sculpture Caballito de Sebastián was exhibited in this square, an object that geometrizes a horse’s silhouette, made with metal and painted yellow, which also works as a drain vent. The geometric abstraction clearly forgets the historical sense of its predecessor. There is no much more to say about this piece.

During the early 21st century, the implementation of an urban program which had been planned years before was put to work, it consisted mainly in placing hydraulic concrete on the streets, concrete plates and rocks in pedestrian areas, placing ramps and pedestrian crossings, greater maintenance to all green areas, and a new lighting system, restoring benches, and the substitution of the central ridge for the current pyramid-shaped figures intertwined, made of concrete.

The Independence Bicentennial celebration was close and, after some issues, the program for the celebrations was defined, which in addition to finishing the restoration and improvement works, included a monument that would be defined through a contest.

The Light Stele was the chosen project to celebrate 200 years since the Independence and 100 since the Mexican Revolution, it was inaugurated in 2012 by La Puerta de los Leones. The piece makes no direct reference to a country’s historical moment. Conceptually, it speaks about modern Mexico, about technology and what comes ahead. A polemic element, which has already become an important part of the urban landscape, although it does not seem to be good enough to be compared with the rest of the main monuments, only history can give its final verdict.

Funnily, at some point, it was considered that the monument to commemorate the Bicentennial would be placed at the Palma roundabout; however, since the late 20th century, movements in favor of nature and some other groups defended the preservation of this element. It is esteemed that this long-lived plant was placed between 1920 and 1930, perhaps during the time it was one of the projected vegetation pieces. This element does not make reference to a historical moment, but it is an iconic element which we have made part of the context. In an unplanned way, it has also turned into a nature protection symbol, issue we need to reflect on these days.

In recent years, we have witnessed the growth of skyscrapers, mainly at the Puerta de los Leones, the landscape here has become an impressive image, one of a great city. Since 2018, one of the Metrobus lines began circulating across one part of the street. Some of the new buildings have their own lighting, and along with the Light Stele and the illumination system have created a new perspective of Paseo de la Reforma by night.

There are many minds, styles, opinions, and circumstances, which have determined the existing objects on this street. The historical elements which have been placed have been selected according to people in charge at the time, and this is how many historical characters and landscapes have been included and many others have been forgotten, a common situation in history; however, we find many symbols when traveling across this street, that talk to us about our country’s different historical periods.

Paseo de la Reforma is a space filled with life, a lattice that tells the city’s story, which transforms as time passes by and leaves a mark of its different stages, since it holds a very complex ecosystem. The elements mentioned here are only a few of the highlights, because this space has also been a forum for the most diverse manifestations, a spot for the most important celebrations, one of the favorite places for taking a stroll, and the perfect setting for books, movies, and everyday stories. We write new stories every day and this is the reason why every time we walk across it, we can be sure that we are becoming part of that history and that ongoing transformation.

COver photo @dronerobert