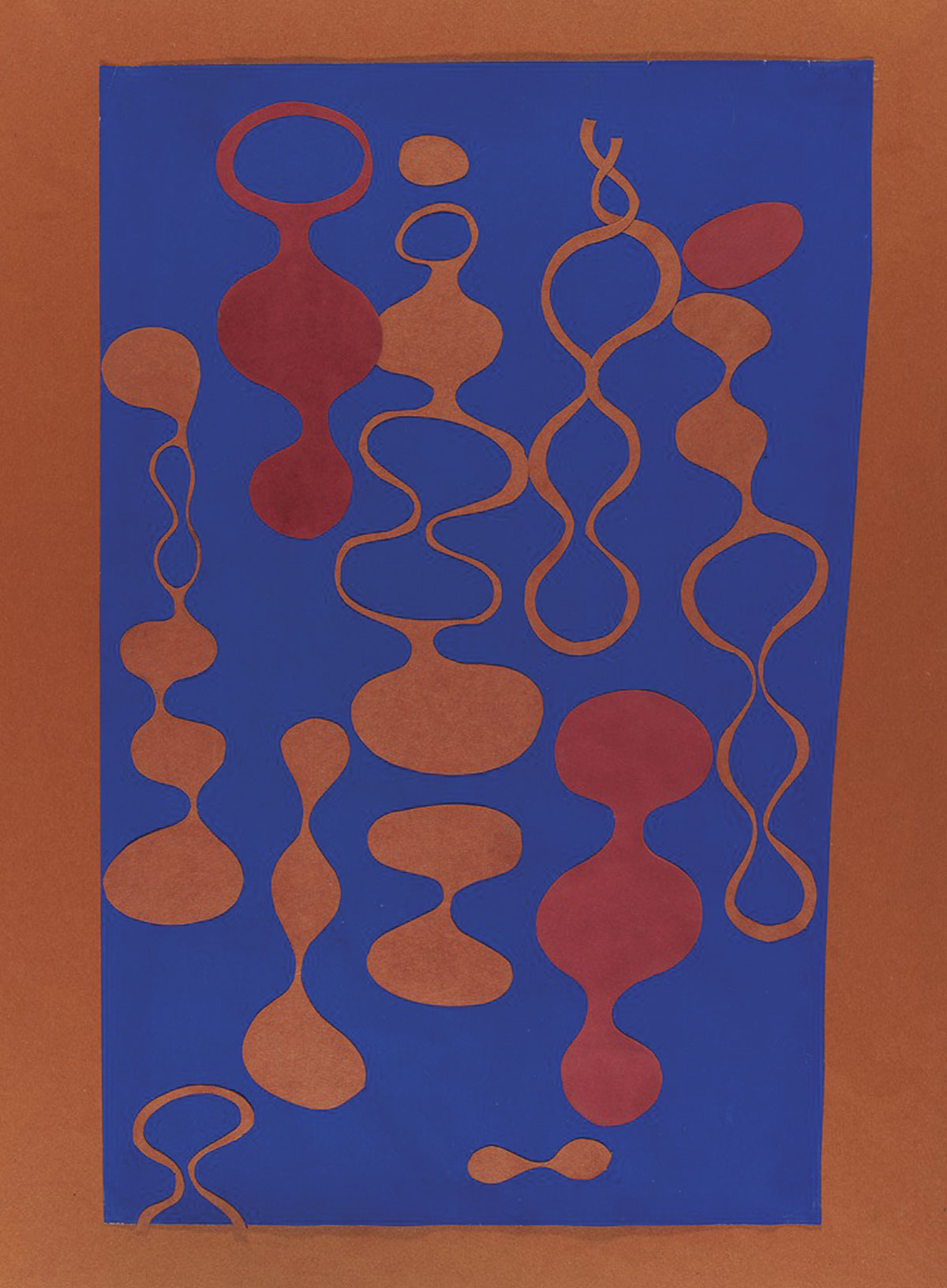

Rebels without a cause or creative people? The bad behaved ones from the time ended up at the Bauhaus, under the terrified eye of the conservatives, who threatened their children with a place for crazy people, who had no future, the extravagant and liberal people of the moment, the rockers before rock n’ roll who today are said to have set the foundations of design. But if a statement could sum up the essence of the 20th century’s most important art school, it would be: “matter shall be learned from its origin”.

In addition to this teachings and of being the source of a new current that made design lighter, by removing heavy decorations, it also gave matter a new voice and marked the relevance of freedom of speech. Mies van der Rohe ended up shutting it down when the German Worker’s Party took over the government and, as a last act of freedom, the director at the time decided to close the school so it did not fall under the demands of the Nazis, who asked for all foreign professors to be fired, the way the book Bauhaus Women: A Global Perspective, explains.

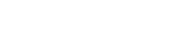

One of the most controversial and advanced topics in the institution were women, flappers of the time, visionaries, the rebels in a sexist era who, with no precedent, decided to take their future and make a work of art of it.

Under a promise of equity, Walter Gropius sent a message inviting these artists to gather at the school, which resulted in 51 women and 61 men, something that had never been seen before. Sooner rather than later, the hopes of a liberal institution were shut down by the fear that it might be considered a feminine art school and, in consequence, this prompted segmentation, “women will be dedicated solely to textiles, poetry, and binding”, Gropius stated back then. Also the speeches of masterminds (Kandinsky, van Doesburg, or Schemmer, just to mention a few) became a constant during that period; women were natural beings, while men were cultural beings. Even Paul Klee published a feature in the school’s magazine on how the male gender could be directly related to creation and intellect.

In his attempt to increase the number of students, Hannes Meyer turned to women again under the ad: “Are you looking for equal opportunities as a student?”. Of course, without ever changing the offer in design and architecture subjects. Many women then decided to rebel and stand out, like Anni Albers, who found her calling thanks to the fact that her goal to specialize in glass was flawed when two years earlier, Gropius set a limit between the specialties they had access to. Her career in this area placed her as one of the most important abstract artists of the time. Another example was Marianne Brandt, who studied painting and sculpture in addition to being the first woman to enter the Metallwerkstatt (metalwork program). And many others, perhaps less known, but also references of this period, like Otti Berger, the weaver; or photographer Lucia Moholy, for example.

The air of the scene started to segregate some kind of syncretism. Women, in search for recognition, started working by the hand of their husbands or partners. An example? Mies van del Rohe and Lilly Reich, the perfect match, they worked together and exhibited a furniture line under the initials of both of them. When the Barcelona Pavilion was presented, Reich showed a house that connected through a wall with Mies van der Rohe’s; her work did not get the proper recognition, thanks in part, to the fact that the Bauhaus director had to migrate in 1938 and in this way, ended their collaboration.

Another couple was the one formed by Walter Gropius and his wife Ise, who worked during her career on a diary (still unpublished) about her experience in the school. She was in charge of her husband’s correspondence, wrote his speeches and features (all based on her manuscripts) and after his death, she continued to work on his behalf.

A total of 462 women were part of the movement, specifically one third of the student body. Anja Baumhoff (Art History and Design professor at Master Design and Media, Hannover University of Applied Sciences and Arts) shares in her book, The Gendered World of the Bauhaus, “the Bauhaus seemed like a pedagogical environment which was not progressive in terms of gender, since it kept the conventional social ways and values (…) and hierarchies within the school, which revealed a network of gender paternalism, authority, power, and inequality”.

THE REASON BEHIND ITS IMMORTALITY

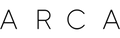

But despite everything, the Bauhaus, was a leap to equity and has remained current for 100 years, but what is its secret? In order to become immortal, first it has to become part of the usual. The current representation is the fundamental piece which, without us realizing it, we suddenly cannot live without. Even so, its greatest piece is an idea, a foundation for design, a memory, a story, and an everyday constant. The most common objects are the result of Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more”. Apple is the brand that proves it, undoubtedly; you can even witness it in a teapot bought at Walmart, its design resembles the ones Brandt presented the world at the time; IKEA manifests under the movement’s rules, their pieces of furniture are basic and have no ornaments. And so it continues. It would not be strange for the Bauhaus name to sound familiar, even to those who are not related to the art scene, since it has turned into a lifestyle, a way of living we would all want to follow: simple, functional, and elegant.

Yet not everything is pretty when talking about the movement, many have criticized it for being dehumanizing and for ending fine arts, and perhaps this is one reason why it started changing during the early 60’s decade. Architects and designers began decorating their works a little more, leading the way for the Post-Bauhaus.

Today we are living in a world that seems to have it all, standing out becomes a challenge, hours pass as seconds, and trends disappear as fast as they were created. This is why we are left with nothing but the questions: how did a current that was formed 100 years ago stayed relevant? Which is the secret and how is it still an exponent in today’s world?

MORE ABOUT BAUHAUS: