Millenary and natural, Japanese architecture is famous for its environmental awareness and the way in which its constructions seem to fit on their own. Japan also stands out for being one of Asia’s most developed areas and a world power, in addition to its cultural legacy.

It can be traced back to year 665 B.C. The emergence of Buddhism in year 538 made Japanese style take a turn, thanks to the number of Korean and Chinese architects that arrived in the country.

Its style is a unique blend with Chinese influence, the use of wood is essential, since it adapts to the different weathers in the area: very cold during winter and hot in summer. Something that stands out in this architecture is the assembly, a structural system that works with wood cuts and joints without the need to use nails, screws, or any other type of union foreign to it. Ancient Japanese artisans introduced the art of simplicity and wood’s own character, thanks to assembly, which, despite the complexity of setting it up, maintains the art behind the cutting, bending, compression, and balance through which the pieces in a construction fit.

One example of traditional Japanese architecture is the Horyu-ji shrine, located in Nara and its construction dates back to the Asuka period (552-710). Its design has never been altered, the deity that represents it is located at the center of the space and is considered the oldest wooden structure in the world.

Another period of this architecture worth mentioning is the Hejan. Here, priest Kukai traveled to China to study Shingon (a form of Vajrayana Buddhism, introduced in year 806), and with this, people began building temples on the mountains to get away from the city bustle; thanks to this, its design became more rustic. Tea houses and the ritual that drives them goes back to the Kamakura period (1185-1333), where constructions focused on the rural home kind, with natural materials and whose weaving became their main weapons.

After World War II, the Japanese style experienced a relevant change: technology and the need to restore were the main reasons. During this time, traditional elements were combined with technological advances; proportions, space, gardens, and the will to urbanize, become fundamental pieces in design, making way to modern Japanese architecture.

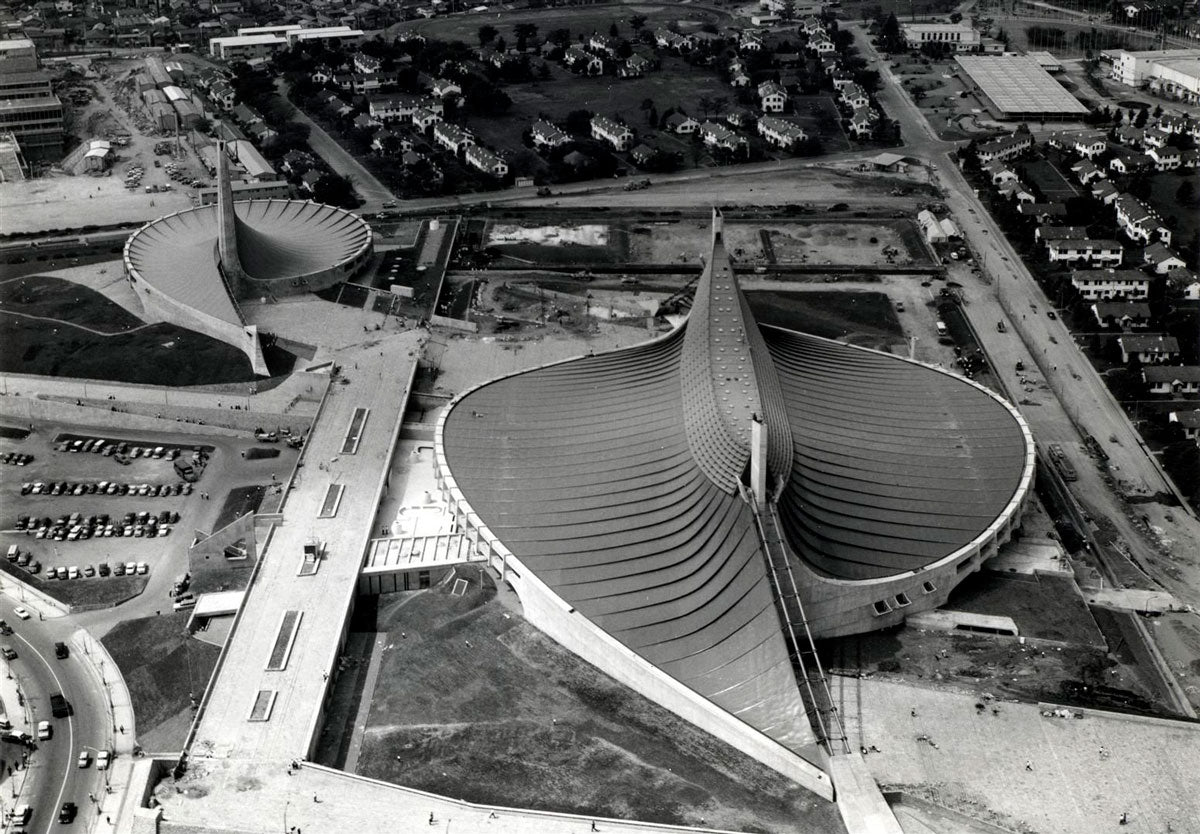

Kenzo Tange is one of the most recognized architects from the time, being responsible for the construction of national gyms for the Tokyo 1964 Olympics. Two buildings, the main one evokes a Japanese pagoda, while the second one, in addition to being smaller, looks like a snail shell; both have become examples of modernism.

Shigeru Ban is another example, known for his innovative use of materials and his “emergency architecture”, which is reflected in his humanitarian efforts; the Nepal Project among them, which consisted in rebuilding homes for the victims of the 2015 earthquake. His career has been recognized with multiple titles, like the 2014 Pritzker Prize, under the quote “a committed professor who is not only a role model for the younger generation, but also a source of inspiration”, becoming the seventh Japanese architect to get it (*). Among his work, New Zealand’s cardboard Cathedral stands out, a simple structure made of paper pipes -equal in length- and six-meter long containers. The pipes are covered in water resistant polyurethane and flame retardant, which the architect began developing in 1986.

Sou Fujimoto established his firm in year 2000 and even though it is recent, his work has stood out for the personal character in each of its projects; among the highlights are: the Musashino Art University Museum & Library (2010), the Children’s Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation in Hokkaido (2006), and the House Before House (2008), a project that reflects on future houses.

These are just some examples of Japanese architecture, which prove that Japan is one of the countries with more history and the leader of modern architecture today.